Tessa Coombes, PhD student in the School for Policy Studies, former councillor, ex-policy director at Business West, and part-time blogger discusses why inequality matters, following the screening of a new documentary at the Bristol Festival of Ideas.

Tessa Coombes, PhD student in the School for Policy Studies, former councillor, ex-policy director at Business West, and part-time blogger discusses why inequality matters, following the screening of a new documentary at the Bristol Festival of Ideas.

“The people will always forget” was a significant line in the documentary The Divide which I saw this weekend as part of the Bristol Festival of Ideas. In the film the line refers to the belief repeated by those to blame for the sub prime mortgage crash in the US, the bankers and financiers, who led us into the Global Financial Crisis and then expected us to bail them out. It’s an assumption that one could well believe our politicians make on a regular basis when taking some of the decisions they do – it’s ok they’ll forget about it when it comes to voting! It’s also an assumption that means we fail to learn from the mistakes of the past and that potentially stops us from addressing many of today’s issues and concerns. Which brings me to the subject of this discussion – the increasing levels of inequality in the UK and the growing divide between top and bottom.

The Divide catalogues the stories of different individuals in the UK and US just trying to get on in life. It highlights all too easily the increasing divide between those that ‘have’ and those that don’t. It illustrates the growing extent to which many of us are perhaps mistakenly driven by money and consumerism, by keeping up with our peers or striving to do better than them, and aspiring for things that are, in the end, unlikely to make us any happier. The main message of the film is based on the book “The Spirit Level” by Richard Wilkinson and Kate Pickett, first published in 2009, but becoming ever more pertinent as time goes on. One of the most important points that the book makes is that inequality affects all of us. The problems are not just confined to the poor, the effects are seen across all aspects of society. Income inequality is a social pollutant because it spreads and everyone is worse off in a more unequal society.

The film illustrated many relevant issues that we are beginning to see the impact of in the UK, but in this post I’m just going to pick up on a couple of them that I think are becoming ever more relevant, that is, the impact of zero hours contracts and the growth of gated communities.

The use of zero hours contracts has become more prevalent in the UK in recent years across a range of sectors. Whilst some in government have tried to argue that it suits both workers and employers, the human impact of these contracts is illustrated particularly well by the film. If you don’t know how many hours you will be working in any particular week how can you budget for rent, food, bills etc? Imagine the levels of stress this type of contract could impose on you from day to day. You don’t know when you will be needed or for how long, so you don’t know what time you need to go in to work, if at all. You don’t know what you will earn in a week, so how can you plan ahead? The insecurity and uncertainly this creates is huge. Imagine having to live with that, even as a single person, but what if you have children and have to plan for their lives too, how does that work? In New Zealand this form of contract has been banned altogether (by a centre-right government), perhaps we could learn something from them?

The concept of gated communities has been around for some time now, with many more at a massive scale in the US, but something that is also creeping into the UK. In the US it’s a way of creating a sanitised community, where white people can feel safe surrounded by other white people, protected by armed guards at the entrance to their ‘community’. The community in the film had its own golf course, lake, play areas and parks and was characterised by large individual houses in their own plot of land. It’s a community that to many would look and feel like ‘prison’ but which in the US is something to aspire to. In the film these places came across as very exclusive, a place to live where people felt safe, but also where people felt isolated. There was in fact little sense of community in evidence, with estate agents promoting the place as lovely and quiet and where you won’t see your neighbours. That’s not a community! In the UK these types of gated community are happening, not on the scale of the US, but they’re there to make people feel safe, so people can surround themselves with other people who have money and status. To me it would feel like a prison, where you have to sign in visitors and go through guard gates just to get home, and where the diversity that makes our communities so rich and fascinating is totally missing. Let’s hope we choose to learn less from the US and focus more on the innovative and creative approach of our European and Scandinavian neighbours.

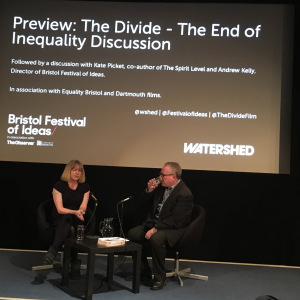

This point on who we learn from is an interesting one, which was picked up during the discussion with Kate Pickett after the film. It seems the devolved administrations of the UK are more likely to look to Scandinavia, The Netherlands and Germany for inspiration, when it comes to tackling inequality, than the UK Parliament as a whole, where sadly, all to often we look to the US for ideas.

That is the US where health and social inequalities are worse than anywhere else and where income inequalities are at their most extreme. There are many lessons to learn from elsewhere but let’s please make sure we are looking in the right direction. For example, in Utrecht, in the Netherlands, they are looking at paying citizens a basic income and in Bhutan a Gross National Happiness Framework was introduced to replace measures based on GDP.

“Inequality destroys empathy” that’s why whilst inequality does of course matter, it doesn’t matter how you achieve greater equality. There are a range of many different measures and policies from across the political spectrum that can work. The key is to do something about top and bottom levels of pay to create greater income equality because as Kate Pickett put it “every action we take individually matters and can make a difference”.