In this blog, Simon Sebire from the Centre for Exercise, Nutrition & Health Sciences and three PhD students reflect on new avenues of research into childhood physical activity and obesity in Low and Middle Income Countries and the opportunities and challenges this work presents.

New ideas emerge in the least likely places. As I listened to Professor Andy Gouldson present his research to the School for Policy Studies in spring 2014, I was inspired to sketch connections between some of Andy’s concepts (economic development and environmental issues) and my own (the psychology of motivating people to adopt healthy behaviours like being physically active). After the talk, I shared my scribbles with my colleague Prof. Russ Jago, only to find that he had an almost identical set.

Our thoughts had independently been transported from Bristol to Mexico and musings about the potential associations of urban development and rural-urban migration on the lifestyle behaviours of children and their families. This international perspective is not something either of us had previously pursued is but clearly had prompted some scribbling! The Mexico connection was inspired by three CONACyT-funded students, from Mexico, who at the time were studying our MSc in Nutrition, Physical Activity and Public Health and were considering PhDs.

Nearly 1 year on the three students (Ana Ortega Avila, Maria Hermosillo Gallardo and Nadia Rodriguez Ceron) are now PhD students in the School for Policy Studies Centre for Exercise, Nutrition and Health Sciences supervised by Prof. Russ Jago, Dr Angeliki Papadaki and I. They secured further funding from CONACyT to pursue their programme of research to study how various social, psychological and environmental factors might be related to physical activity and nutrition behaviours in children adolescents and their families in Mexico.

The causes of and response to increasing levels of obesity in low and middle income countries have been the focus of a recent Guardian Global Development Podcast. The podcast draws on the experiences of children, families, health practitioners and campaigners from South Africa and Mexico. In Mexico 73% of men, 69% of women and approximately 35% of adolescents are obese or overweight which is higher than in the USA. It is clear that there is much to be done to both treat those who are already overweight and prevent the development of obesity in young people. However, extrapolating our existing research and knowledge of what we think drives obesogenic behaviours in places like Bristol to the context of people’s lives in Mexico presents a number of challenges.

Ana, Maria and Nadia have a wealth of experience from previously working in Mexico as nutritionists or within the food industry, so I asked them to listen to the podcast and share their insider’s view of the challenges ahead:

Maria referred to the potentially damaging effects of families in Mexico aspiring to an American lifestyle dominated by unhealthy foods and sedentary behaviour:

The blog says that processed foods and junk food are one of the main causes of overweight and obesity increasing in Mexico, which is partially true, but I think it has to do a little bit more with what I call “junk behaviours”. For example, how mums from rural areas prefer to give their children processed foods instead of home-made meals because they heard somewhere that people from USA consumed them, and because Americans always choose right (at least that’s the belief in some parts of Mexico); junk food and processed foods are the way to go for feeding their children.

Ana suggested that this influence may be strongest in regions closest to America and highlighted the broader problems associated with researching an issue which is geographically diverse:

Mexico is among the largest countries in the world geographically and demographically (118 million people); where differences in dietary pattern exist between rural and urban areas or between north, central and south regions.I have always lived in the northwest and the influence of the U.S.A. is visible in a lot of aspects in our life compared to the centre or south of the country. Our dietary patterns are based on American food choices and less on the Mexican traditional diet.

Ana, Maria and Nadia all added that the potential mismatch between perceptions of wealth and health may be making being overweight an aspiration:

Ana: In my experience as a nutritionist there are a number of cultural misconceptions among population when it comes to healthy nutrition. For example, being a little overweight still means you are healthy and well-nourished whereas being thin means you are unhealthy or sick. People don’t see overweight as a problem, on the contrary, they see it as something normal.

Nadia suggested that such perceptions may prevent parents from identifying obesity as a potential health problem in their children:

I think the healthy body image is distorted as family, friends or in the streets, the most common thing is to see someone obese; and that is really concerning because how will they do something to improve their health if they don’t even think there’s a problem.

Ana, Maria and Nadia reflected on the challenges of applying our physical activity and nutrition research findings which are largely based on evidence from developed countries such as the UK or USA to the context of middle income countries such as Mexico. A good example is parents’ perceptions of safety when letting their children play outside of the home. In UK research, including some in Bristol by my ENHS colleagues, we tend to focus attention on the presence of traffic or children’s risk of injury while unsupervised. In contrast, perceptions of safety in Mexico are measured nationally with questions including those related to the risk of kidnap, existence of violent gangs in the neighbourhood, armed robbery and frequency of firearms shootings. 73.3% of the participants in the 2014 National Survey on Victimization and Perception of Public Safety (ENVIPE) in Mexico reported not feeling safe in their local areas. In addition to the safety implications of conducting research in this context, it is clear that current measures of parents’ perceptions of their child’s safety to be active outside the home will not be sufficient and Nadia has plans to develop a new tool.

In addition, the political landscape challenges us to consider different ways in which our research may be best able to impact on health policy:

Ana: The political context in Mexico is complex, the government is dealing with high levels of insecurity and corruption, events that prevent the government from focusing on other matters such as the implementation of new health policies.

Maria believes that more is needed to be done to educate policy makers in addition to the public: There is a huge educational barrier, both governmental and individual, which makes difficult to take seriously the obesity and overweight problem.

Nadia: All those factors are completely different to high-income countries, and makes the context a complex matter to understand when almost all the research has developed in a completely different contexts with a wider range of opportunities to change or create policies that have a real impact in the population’s health.

In summary, over the last year or so, I have been transported from Bristol city to Mexico City thanks to a fortuitous combination of research daydreaming and inspiring MSc (now PhD) students. As a supervisor, my initial conversations with our new students has forced me out of my research comfort zone, an experience which has been echoed and reported by researchers in the International Physical Activity and the Environment Network in Latin America. Undoubtedly, our success in co-producing research which could have international impact will require us to work together to combine our collective knowledge to understand the context and key drivers of obesity-related behaviour change in Mexico.

Thanks to Ana Avila Ortega, Maria Hermosillo Gallardo and Nadia Rodriguez Ceron for their contributions.

- Ana’s PhD focusses on the development of a social media intervention to reduce consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages in Mexican older adolescents

- Maria is studying the associations between urbanicity in Mexico and lifestyle behaviours and the influence of the rural urban transition on family health.

- Nadia’s PhD focusses on the environmental and social correlates of physical activity in children in Mexico City.

Dr Simon Sebire is Lecturer in Physical Activity & Exercise Psychology in the Centre for Exercise, Nutrition & Health Sciences (ENHS) in the School for Policy Studies.The results of the 2014 Research Excellence Framework (REF) confirm the Centre’s international reputation for research excellence within the field of physical activity, nutrition and health. ENHS was rated 1st overall in the UK.

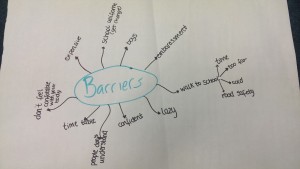

Recently a group of Year 8 students from Bridge Learning Campus spent the day with staff in the centre for Exercise, Nutrition, and Health Sciences. Two of the girls (Amy Manning and Jess Martin) were winner and runner-up respectively of the Bristol Bright Night (Healthy Bodies, Healthy Minds) award. As part of their prize Mark Edwards (ENHS) and Chloe Anderson (Centre for Public Engagement) arranged for the girls to visit the health-focused Centre. Mark reflects here on the fun and insightful day that ENHS spent with the girls.

Recently a group of Year 8 students from Bridge Learning Campus spent the day with staff in the centre for Exercise, Nutrition, and Health Sciences. Two of the girls (Amy Manning and Jess Martin) were winner and runner-up respectively of the Bristol Bright Night (Healthy Bodies, Healthy Minds) award. As part of their prize Mark Edwards (ENHS) and Chloe Anderson (Centre for Public Engagement) arranged for the girls to visit the health-focused Centre. Mark reflects here on the fun and insightful day that ENHS spent with the girls.