Alex Marsh reports on an event at the Bristol Festival of Ideas. This post first appeared at PolicyBristol Hub.

How should a world characterised by increasingly complex interdependence be governed? If most of the major challenges we face have no respect for the artificial borders marking out nation states, how can we identify and deliver effective solutions?

How should a world characterised by increasingly complex interdependence be governed? If most of the major challenges we face have no respect for the artificial borders marking out nation states, how can we identify and deliver effective solutions?

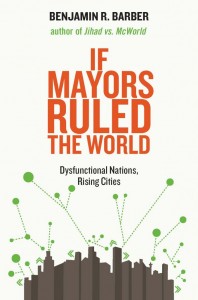

The answer Benjamin Barber offered in his stimulating presentation on Monday night is that we need to look to cities. More specifically, we need to look to mayors. His case is in part rooted in the fact of an increasingly urban future. But it is also based upon the characteristics he identifies as distinctive to mayoral governance. This is an argument developed at greater length in his new book If mayors ruled the world: Dysfunctional nations, rising cities (Yale University Press).

Barber starts from the premise that we can no longer look to the nation state to find solutions to some of the world’s most pressing problems. The nation state may have made sense when social and economic problems were contained within borders. That is not the world we inhabit now. Even if a problem starts as local, it can soon become global.

But in a world of interdependence the community of nations has time and again proved itself unable to deliver an effective response. Whether it be policy on climate change, security, migration or public health, attempts to find cross-national solutions are as likely to result in stalemate or veto by individual sovereign states as they are to result in decisive action. When problems demand collaborative solutions, nation states can find it hard to move beyond their competitive impulses.

Equally importantly, nation states fail to secure the sort of broad-based democratic support that is necessary to deliver legitimacy to radical solutions. This is because of the limited and rather abstract nature of national citizenship. It is a citizenship of rights, without meaningful obligations that have an everyday urgency.

Barber contrasts this with the way in which mayors operate. Models of mayoral governance differ in their detail, but their defining characteristic is pragmatism. Barber’s argument has a strongly structural flavour. He argues that for mayors “issues shape behaviour in common ways” and that “ideology doesn’t serve them very well; and nor do political parties”. Mayors need to find solutions to real problems that affect the day to day lives of hundreds of thousands of people. (more…)