Dr Simon Sebire, Centre for Exercise, Nutrition and Health Sciences, reflects on the success of the physical activity initiative, The Daily Mile.

Ten days ago I had the pleasure of being involved in the launch of The Daily Mile in Guernsey. The Daily Mile has been taken on by most schools on the Island in the last 9 months and Thursday 24th June was a celebration of the work here to date. Elaine Wyllie, the founder of The Daily Mile and John, Elaine’s husband, were in Guernsey to support the launch. This included a tour of Daily Miles at various schools around the island, a celebration mile and lunch and a special mile for some pupils around the beautiful Government House (the residence of the Lieutenant-Governor, the Crown’s personal representative in the Bailiwick of Guernsey).

It was whilst walking the mile around the Government House grounds (being lapped by happy, rosy-cheeked children in the process) that Elaine and I began discussing how my research on people’s motivation for physical activity and developing interventions could help explain why children and schools in Guernsey and around the world seem so taken by The Daily mile phenomenon.

Elaine explained her take on this by beginning the following conversation:

Elaine: Think of a happy memory you had as a child, but don’t tell me what it is.

Me: (thinking…)

Elaine: Now tell me, were you inside or outside?

Me: Outside

Elaine: Were you on your own or with others?

Me: With others

Elaine: Were you in the supervision of adults?

Me: Sort of … at a distance

(By the way, my happy memory was of when I was 7 or 8, a hot summer day, building a sand boat with family and friends to sit in as the tide rose up Port Grat beach in Guernsey. I was outside, with other children and parents were involved sporadically, but letting us play freely.)

In identifying a happy memory, Elaine had just revealed some of the core principles of The Daily Mile. These include a focus on having fun, being non-competitive, being outside and in nature, connecting with other pupils/teachers, being a simple intervention, being fully inclusive and owned by the children (i.e., jog or run at their own pace).

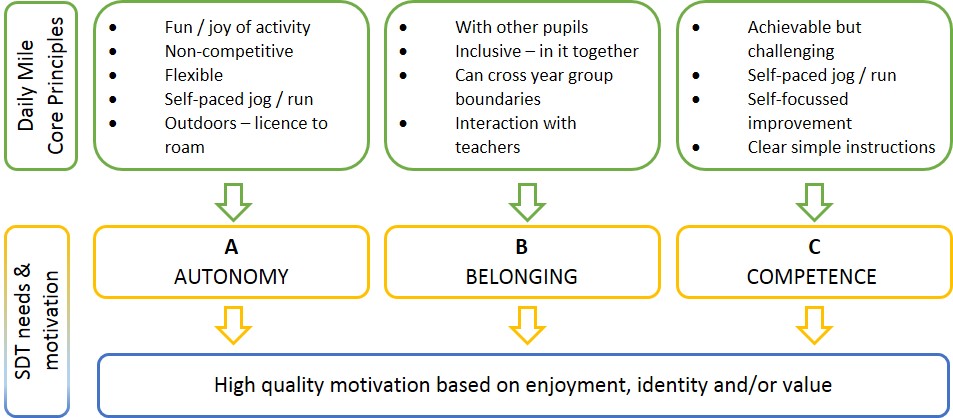

These core principles chime with the fundamental elements of much of my research into physical activity motivation. Using a psychological framework called Self-Determination Theory (or SDT) I have studied the foundations of and outcomes linked with high quality motivation for physical activity in children and adults. According to this approach, a person’s motivation is deemed to be high quality when it is autonomous, in other words when motivation stems from the enjoyment of being active, the satisfaction one gets from being active (or doing a mile), a feeling that being active is in harmony with a person’s sense of who they are, or that being active brings them personally valued benefits (e.g., meeting pupils in other year groups or getting fitter). People have these kinds of motivation for being active when they experience SDT’s core principles; Autonomy, Belonging and Competence (A, B, C).

Autonomy: Feelings of volition, freedom, choice, ownership and empowerment

Belonging: Feeling strong connections with others, included, understood and respected

Competence: Feeling capable, able to master a skill or task.

Importantly, according to the theory, we need to experience the A, B and C in our daily lives, interactions and activities to have optimal well-being, development and functioning.

In a number of studies (referenced below) over the last 10 years or so, my colleagues and I have found evidence to support the idea that when children and adults feel that their A, B and C is satisfied when thinking about being active, they experience high quality, autonomous motivation and that this is linked with greater physical activity. Common to all of these studies is the finding that motivation based on enjoyment and/or personal value is linked to physical activity, whereas motivation based on guilt or external pressure (such as rewards, or demands from others) is not. Accordingly, we have designed a number of physical activity interventions for children and adolescents with the A, B and C of motivation in mind.

When viewing The Daily Mile through this motivational lens, it is possible to see how the intervention expresses the A, B and C:

Of course, my retro-fitting of SDT principles to The Daily Mile is just one lens through which to study its broad appeal and apparent motivating effect on pupils. However, it is entirely possible for interventions which grow from the ground up to align in many ways with what is known from behavioural or psychological sciences even if they did not set out to do this from the start. Aligning the core principles of The Daily Mile with a framework such as SDT’s A, B, C may also allow the intervention to stay faithful to its design as it is adopted and potentially adapted in schools around the world.

I would argue that unknowingly, when implemented in line with its core principles, The Daily Mile could be tapping in to a well-known, evidence based and positive source of motivation for physical activity. At its core The Daily Mile is simple. Perhaps it is as simple as A, B, C.

Dr Simon Sebire is Senior Lecturer in Physical Activity & Public Health in the School for Policy Studies at the University of Bristol. He is also Interim Chief Executive of The Health Improvement Commission for Guernsey and Alderney.

References

- Are parents’ motivations to exercise and intention to engage in regular family-based activity associated with both adult and child physical activity?

- Testing a self-determination theory model of children’s physical activity motivation: a cross-sectional study.

- Predicting objectively assessed physical activity from the content and regulation of exercise goals: evidence for a mediational model.

- Examining intrinsic versus extrinsic exercise goals: cognitive, affective, and behavioral outcomes.

- What motivates girls to take up exercise during adolescence? Learning from those who succeed.

- Does exercise motivation predict engagement in objectively assessed bouts of moderate-intensity exercise? A self-determination theory perspective.