These blogs and policy briefs were co-authored by multi-disciplinary teams of students on the MSc in Public Policy (MPP), Migration, asylum and human rights: UK, EU and global policy perspectives unit. The blogs and briefs were prepared in discussion during class and finalised by the students outside the formal teaching programme. The exercise proved to be very popular. It provided experience of team-work, collaborative research and practice in writing clear and concise text for public and policy audiences – Ann Singleton, Reader in Migration Policy.

This policy briefing was written by Verónica Arbeláez, Ana-Maria Crețu, Paulo Vitor de Paula Medeiros de Matos. With contributions from: Juju Eom, George Haines, Nia Lake, Andrea Alvarez Ojeda, Julie Ren, Grace Whittaker

Advisor: Nadine Finch, Honorary Senior Policy Fellow, School for Policy Studies and Migration, Mobilities Bristol Specialist Research Institute.

The issue

Since July 2021, 4,600 asylum-seeking children have arrived in the UK unaccompanied by a parent, carer, or legal guardian. According to the UNHCR (1994), an unaccompanied child is anyone under eighteen who is “separated from both parents and is not being cared for by an adult who by law or custom has the responsibility to do so”.

Migrant children, often rescued at sea by lifeboats, come to the UK unaccompanied for several reasons. For instance: i) their parents might have been murdered, incapacitated, or detained; ii) they might be afraid of persecution in their country of origin; or, iii) they might flee to avoid being forced to fight as a child soldier (The Fostering Network, 2023).

Upon their arrival in the UK, unaccompanied asylum-seeking children (UASC) have been placed in Home Office-rented hotels without being referred to or accepted for accommodation or assistance from local child protection agencies, in line with the Children Act 1989[1]. Many children housed in these facilities have gone missing. As of 21st July 2023, the number of missing children stood at 154 (Jenkins, 2023).

Defining “missing migrant children” is problematic. It is often difficult to differentiate between missing children and missing data. Death is not the only way a child may disappear during or after migration. Fear of apprehension, deportation or other sanctions can lead UASC or migrant children to develop ways to remain under the radar (Sanchez, 2018). Further, the ‘Care of unaccompanied migrant children and child victims of modern slavery’ (Department of Education, 2017), a statutory guidance for local authorities, points out that in some instances, UASC go missing due to uncertainties over their migration status or feeling unsupported by the relevant authorities that are looking after them. In such cases, the role of the social worker is pertinent to ensure children feel protected (Department of Education, 2017).

UASC are also vulnerable to exploitation for various illegal and harmful purposes. Recent reports suggest that girls are generally targeted for sexual exploitation, while boys are used in drug trafficking operations (The Guardian, 2023a). However, children are trafficked for other forms of criminal exploitation[2] and boys have also been subject to sexual exploitation[3].

The majority of the children who have gone missing recently are Albanian boys. Some are being ‘abducted off the street’ and ‘bundled into cars’ and are most likely recruited into county-line operations (The Guardian, 2023b). Traffickers use a variety of strategies such as targeting the hotels where children are placed, making promises of lucrative employment or education, threatening family members back home or keeping children accountable for previously incurred family debt. Human trafficking is also organised through close family or social ties, where the victims are recruited, manipulated, or threatened for financial gain (Davy, 2022). Overall, human trafficking is caused by overlapping and interconnected factors, including both individual and structural contexts, as well as country-specific circumstances which place children in vulnerable situations (Hynes et al., 2019).

Vulnerability and exploitation

Currently, the UK faces an unprecedented rise in missing migrant children who arrived and applied for asylum, only to be housed in hotels by the Home Office without being formally referred to local authorities’ child protection agencies. Whilst the Government claims that placing the children in hotels was the safest and only viable option, it has generated controversy. A report from the Independent Chief Inspector of Borders and Immigration has highlighted that concerns have been raised about the lack of DBS checks for hotel staff with access to master keys, particularly those residing on-site and responsible for the safety of minors (Neal, 2022). This is not a new problem. According to the Ofsted report, ‘Missing Children’, cited by The Department of Education (2014), other factors were responsible for the missing children situation, including the lack of appropriate risk management plans, limited communication and collaboration between the Home Office and local authorities, and the instability of the placements where these children are placed.

Being unaccompanied adds an extra layer of vulnerability for migrant children. The Home Office asserts that the children are not being detained in hotels, as they can leave their accommodation. However, the absence of assigned social workers and the lack of services usually offered to protect children in vulnerable situations put them at risk of being trafficked for criminal exploitation. In particular, they risk being coerced into engaging in criminal activities like street crimes, benefit fraud, drug production and distribution and the sale of counterfeit goods. Being exposed to such activities places the children at risk of being arrested for crimes arising from their exploitation and, further, to harmful changes in status from asylum seekers or victims of child trafficking to apprehended criminals. Becoming the victim of human trafficking seriously threatens migrant children’s physical and psychological well-being and life chances. Furthermore, when criminal gangs recruit children, it is difficult to track their whereabouts, making their retrieval, as well as data collection, exceedingly difficult.

Where are the missing children now?

In October 2022, the Minister of Immigration, Robert Jenrick, initiated a multi-agency persons protocol, which involved the collaboration of the police and local authorities, to locate missing children (UK Parliament, 2023). Later, the Missing After Reasonable Steps, or MARS protocol, was followed for children who disappeared from hotels. Finally, the Home Office and the Department of Education established a task force dedicated to UASC, aiming to devise strategic solutions for ensuring their safety (UK Parliament, 2023). Despite these efforts, 154 children are still missing (Jenkins, 2023) without any information regarding their whereabouts (BBC, 2023a).

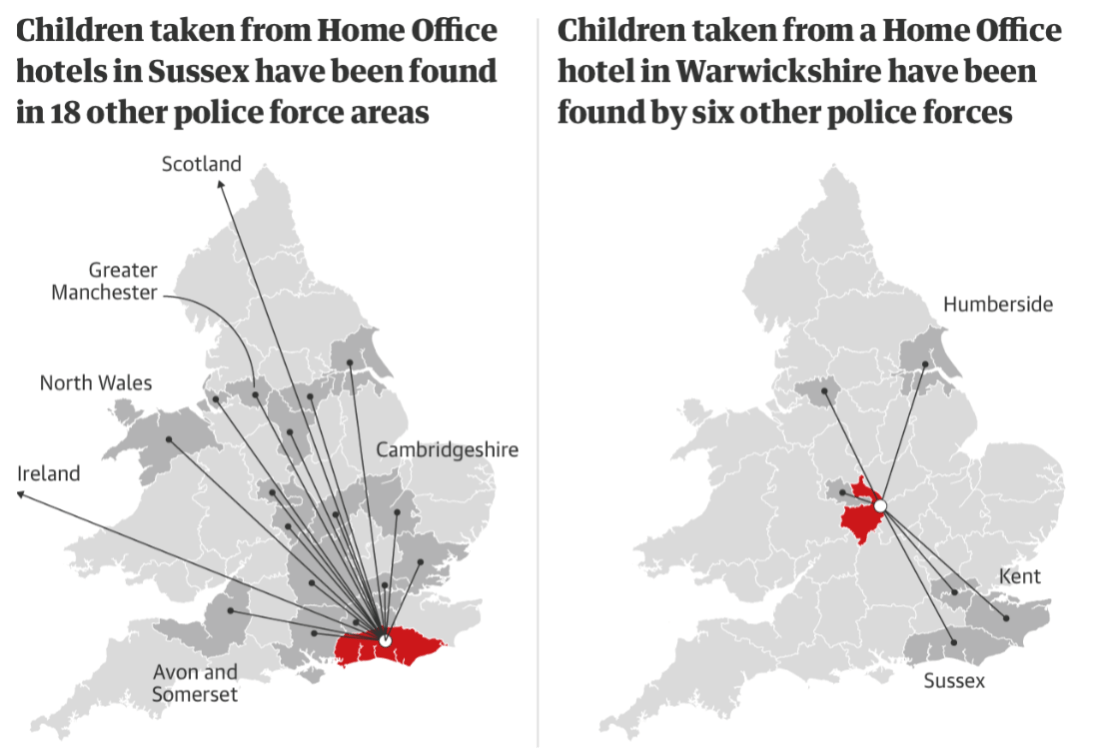

IMAGE 1: ENGLAND MAP SHOWING PLACES WHERE CHILDREN WERE FOUND

Source: The Guardian (2023d)

Some of the UASC were found in various parts of the UK, whilst others are still missing. There have also been allegations against certain police forces, with one whistleblower, claiming that the investigations are ‘cursory at best’ and that very few children have been recovered and returned (The Guardian, 2023d). Meanwhile, the Home Office rebuts the claims that UASC are being kidnapped as “not true”. The Home Office‘s denial of kidnapping allegations is, however, based on not counting children who are recruited, rather than abducted, as being kidnapped.

Britain expects 3,000 to 4,000 UASC to cross the channel in small boats this year (PBS, 2023). This is a worrying forecast given that 200 asylum-seeking children have already gone missing and that retrieval efforts have been ineffective since 154 children are still missing. Further, this forecast highlights the urgency of better protocols for the accommodation and protection of vulnerable migrant children.

Media coverage

The UK Home Office has been aware of the increase in missing UASC since July 2021 (Brennan and Isaac, 2023). Media coverage of this issue broke in January 2023, with different media outlets displaying varied levels of sympathy regarding migrants and asylum seekers, a trend already identified in a report commissioned by the UNHCR in 2015 (UNHCR, 2015). The report found that the British media’s predominant themes in articles regarding migrants were the perceived threat they pose to the welfare system and the ‘culture’ (UNHCR, 2015). Most media coverage of the migrant crisis in the UK was found to be more damaging than in other countries, primarily due to aggressive right-wing campaigns (UNHCR, 2015). Deep-rooted anti-immigrant sentiment was also a significant aspect of the Brexit campaign (Blinder and Richards, 2020).

Although the Home Office has been aware of migrant children going missing from hotels (Brennan and Isaac, 2023), conversations in Parliament surrounding this matter have primarily been instigated by MP Caroline Lucas of Brighton and Hove. The issue has since received the support of many other MPs across different parties.

Whistleblowers have nonetheless stated that the Home Office is not doing enough to address this issue nor to trace the movements of the missing children or the criminal organisations previously identified by the local authorities (The Guardian, 2023d). The Home Office has been reluctant to comment even after the news broke.

Culpability and accountability

It has been challenging to establish who is accountable for the problem of missing migrant children in the UK due to repeated attempts of relevant authorities to swerve responsibility. According to longstanding child protection norms, the burden of looking after vulnerable children would be with the region’s local authorities. However, due to the “unprecedented rise in dangerous channel crossings”, the UK’s asylum system has been deemed to be under too much pressure, allowing “no alternative” but to use hotels to house UASC whilst long-term accommodation is arranged (The Guardian, 2023d). Accordingly, a mandatory National Referral System was established by the Government so that children can be referred to local authorities with the capacity to accommodate and support them (NTS, 2022). The National Referral System does not, however, function appropriately. For instance, the Home Office has constantly undermined the responsibility of local authorities to provide accommodation and other services to UASC, and stepped in without due protocols, a situation which resulted in children going missing. Further, there are limitations to who can fall in the category of UASC, either because their home countries are not deemed at risk or due to the unclarity of their age, with some children approaching the age of 18.

It is unclear why the above justifications provided by the Home Office have not been further questioned, considering that the Home Office’s decision to directly provide accommodation for migrant children clearly violates the Children Act 1989, which stipulates that the care and protection of children without a parent or legal guardian must always be the responsibility of the local authorities (Children Act 1989). The Home Office’s assumption of control makes it challenging to hold any specific local authority accountable, despite inadequate adherence to child protection safety measures. A Home Office spokesperson has referred to the well-being of the children as “an absolute priority” where “robust safeguarding measures” are being undertaken to ensure their protection (The Guardian, 2023c). In reality, robust protections have not been adequately followed and implemented.

Existing policies

The UK government guidelines on processing UASC are legally rooted in several UN conventions, human rights acts, and immigration regulations (Home Office, 2020). Echoing the guidelines of UNHCR, part 11 of Immigration Rules (asylum) requires special protection, prioritisation, and safeguarding training for the local authority responsible for UASC (Home Office, 2020).

Asylum applications used to be made at the initial port of entry or at the Asylum Screening Unit, where personal information was gathered along with fingerprints for those over the age of five and interviews regarding their claim for those over twelve. A legal representative or a case worker supported the process. However, even with such measures, many UASC fell through the cracks, with many being denied refugee status[4], and others being deemed to be adults and being removed to a third country after being in immigration removal centres for periods longer than 30 days without access to legal aid.

The 2022 Nationality and Borders Act made UASC more vulnerable to various forms of trafficking as they could be treated as adults and would have a limited timeframe to present their case with additional requirements of information concerning their situation (ECPAT UK, no dateA).

Duty of care

According to the International Organization for Migration – IOM (2016), there are at least three primary State obligations and principles to protect children, including migrant children: the parens patriae doctrine, the obligation to not discriminate, and the best interest principle. The first principle establishes that the British Crown is the ultimate guardian of persons unable to defend themselves, including children within its jurisdiction (IOM, 2016). The second principle was developed in 1989 by the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) and ratified by the UK, which determines that children’s rights should not be undermined due to “the child’s or his or her parent’s or legal guardian’s race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or another opinion, national ethnic or social origin, property, disability, birth or another status” (Article 2 of the CRC). The third principle states in Article 3(1) of the CRC that “In all actions concerning children, whether undertaken by public or private social welfare institutions, courts of law, administrative authorities or legislative bodies, the best interests of the child shall be a primary consideration”.

Beyond these obligations, the State is compelled to observe other civil and political rights that acknowledge the fundamental dignity and potential vulnerability of all persons, especially children under 18 years old, beyond their nationality or status in the UK. These rights include the right to life and to be heard, recognising both the dependency and the agency of children (IOM, 2016).

The UK participated in the first international agreement on people’s movements in 2018, known as the Global Compact for Migration, which addressed specific protection measures for migrant children. Some of these measures included ensuring legal representation and guardianship to all UASC and coordinating international efforts to prevent the children’s disappearance and to find missing children (IOM, 2016).

But despite the numerous laws, commitments, treaties, and conventions ratified by the UK, governments in power have historically evaded their responsibilities based on legal interpretations or reservations which deny UASC their fundamental rights, including giving them access to protective care or providing them safe and legal entry on the territory. Despite previous reservations about CRC being dropped, robust safeguards and clear responsibilities are still inadequate for dealing with the influx of UASC in the UK.

The Statutory guidance on children who run away or go missing from home or care published by the Department of Education on 17th of January 2014 and last updated on 20 May 2020, guides the Runaway and Missing From Home and Care (RMFHC) protocol. This guidance assigns direct responsibility to local authorities in nominating a senior children’s service manager to monitor the policies and situation of children going missing from home or care. Also, the Local Safeguarding Children Boards must monitor the data and reports concerning missing children. The local authority, along with the police, are responsible for analysing the data available and assessing patterns that indicate risks and concerns of missing children. In finding the missing children, an inter-agency framework is followed to classify the degree of risk the children face when missing from home or care. Children are classified as high risk when there are substantial grounds for believing that the child is in danger or a state of vulnerability.

An explanation for why the children go missing could relate to the amount of time (longer than 30 days) the children are placed in hotels rented by the Home Office instead of being transferred to the care of local authorities. Reports suggest that children are being cared for in hotels for longer than 30 days, even though according to the NTS Protocol for Unaccompanied Asylum-Seeking Children Version 4.0 (updated on 05 September 2022), all transfers of UASC from the Home Office to local authorities should take no longer than five working days. These transfers should be made to local authorities such that the number of children transferred does not exceed 0,1% of their general child population[5] (NTS, 2022).

The transfers to local authorities should be made with due consideration of the child’s best interests and the appropriateness of the receiving local authority (UNHCR, 2021). Nevertheless, the decision to transfer the children to a local authority does not consider the authority’s ability to properly care for the children (NTS, 2022). When a child goes missing, the local authority caring for the children at the time it went missing has the legal responsibility to search for the children according to the Statutory guidance mentioned above.

The funding instructions for local authorities regarding UASC for the period of 2022 to 2023 clarify the conditions under which the Home Office provides financial support. Local authorities responsible for UASC with a volume equal to or exceeding 0,07% will receive an allocation of £143 per person per night, whilst local authorities responsible for less than 0.07% will receive £114 per person per night. If children turn 18 years old or go missing for longer than 28 days, the Home Office will cease payments. If there is any doubt regarding the person’s age, relevant payments will be made until proven they are older than 18. For the payments to be made, the local authorities must make a monthly application which includes accurate details of the children supported. However, funding is cancelled when children go missing, so helpful resources that could provide innovative technology and search strategies to find the children more effectively are limited.

The guidance also sets out steps for local authorities to plan for the provision of support given to children who arrive in the UK unaccompanied and could potentially become victims of modern slavery. According to the guide, modern slavery includes “human trafficking, slavery, servitude and forced or compulsory labour” (Department of Education, 2017:12).

The case of missing UASC has exposed the inadequacies of the UK system to receive and care for vulnerable children. Given the ongoing global refugee crises, better safeguards and policies are needed to prevent further unaccompanied asylum-seeking children from going missing.

Source: Anahita Hossein-Pour/PA

Policy recommendations

Recommendations for the UK Government

- Offer basic safeguarding and cease child detention

- End the use of hotels for unaccompanied asylum-seeking children;

- Transfer unaccompanied children seeking asylum to long-term care within the local authority child protection system.

- Instate a clear division of authority and responsibility

- Collaborate closely with local authorities to expand available placements and allocate sufficient funds to local councils for each accommodated child (BBC, 2022);

- The transfer plan to local authorities should include other factors such as infrastructure and service capacity, capability, and quality, in addition to considering whether the proportion of children in the local authority population is below 0.1% (NTS, 2022).

- Implement robust safeguarding protocols

- Conduct comprehensive investigations in areas where child trafficking and criminal gangs are known to operate;

- Make special efforts such as coordinating data collection and analysis within countries and across borders, utilising methods like survey-based data collection, GPS monitoring, and fingerprint capture to identify and refer unaccompanied children (KIND, 2020);

- Apply ethical guidance and standards suitable for working with children throughout the research, survey and data management and reporting process (IOM, 2019);

- Improve information sharing by collaborating with relevant researchers, NGOs, journalists, and other stakeholders across regions and sectors.

Recommendations for Media

- Play an active role in helping the public understand and respond to the issue of unaccompanied asylum-seeking children

- Making the disappearance and plight of asylum-seeking children the “new normal” in news reporting, as well as mainstream political media coverage, can have a detrimental transnational impact (Cooper et al, 2021);

- Design a media strategy to direct public attention to finding the missing children.

Comments on Illegal Migration Act 2023

Parts of the Act came into force on 20 July 2023, and the content of this brief was largely written before that date. The contents of the Act are likely to place UASC at considerably high risk.

- The Act will potentially put UASC at greater risk since it will lead to the creation of other clandestine routes that could encourage more cases of child trafficking.

- Children placed in hotels by the Home Office will feel less protected and unsupported by the State, leading to more significant cases of children missing.

- Under the Act, children who enter or arrive in the United Kingdom without a visa or other permission will not be entitled to apply for asylum but will be removed from the United Kingdom when they turn 18.

- Protection for victims of child trafficking will be decreased.

- The Secretary of State for the Home Department will have the discretionary power to remove a child from the United Kingdom before they turn 18.

- The Act does not resolve the ambiguity about whether the Home Office or local authority children’s services are responsible for caring for the unaccompanied children, and the Home Office has a new power to move unaccompanied children between the Home Office and local authority accommodation.

[1] At the time these actions were undertaken by the Home Office, the Home Office did not have legal authority or power to provide unaccompanied migrant children with accommodation. Under the Children Act 1989, such powers rested with the local authorities, not the Home Office. The Illegal Immigration being discussed currently in the House of Lords would provide additional powers to the Home Office over local authorities, stating that: “The Home Office would be given powers to provide or arrange for the provision of accommodation and other support to unaccompanied children who are within the scope of the duty to remove, and to transfer a child from Home Office accommodation into local authority care” (Gower, A et al., 2023: 6).

[2] See also Child Trafficking in the UK 2021: a snapshot, Independent Anti-Slavery Commissioner & ECPAT UK

[3] The Silent Victims of Human Trafficking, Anti Trafficking International Males: The Silent Victims of Human Trafficking – Anti-Trafficking International (preventht.org)

[4] The percentage as successful grants of asylum are likely to be dictated by country of origin. For instance, a child from Syria has a very good chance of being granted asylum, whilst a child from Pakistan or Albania stands a poor chance. Additionally, many of the Albanian children are likely to be children who have been trafficked as opposed to asylum seekers per se.

[5] The Home Office launched the National Transfer Scheme in 2016 as a response to pressure on some local authorities due to the increased number of UASC arriving in the UK. This scheme allows for an equitable transfer of UASC to each municipality to avoid bringing the primary responsibility of care to a single city.

References

Blinder, S. and Richards, L. (2020). ‘UK Public Opinion toward Immigration: Overall Attitudes and Level of Concern’. rep. Oxford, UK: The Migration Observatory.

Brennan, E. and Isaac, L. (2023) ‘Hundreds of child asylum seekers have gone missing in UK’, Government admits, CNN. Cable News Network. 24 January 2023, Available at: https://edition.cnn.com/2023/01/24/uk/uk-migrant-children-missing-gbr-intl/index.html [Accessed: 13 March 2023].

BBC (2022) ‘Channel migrants: 116 children missing from UK hotels’. [Online], BBC, 13 October 2022, Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-63231470 [Accessed: 13 March 2023].

BBC (2023a) ‘Brighton council seeks urgent talks over missing migrant children’. [Online], BBC, 23 January 2023, Available at: https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-england-sussex-64378482 [Accessed: 1 March 2023]

Children Act 1989 (1989). ‘UK Public General Acts’. Available at: Legislation.gov.uk [Accessed: 13 March 2023]

Cooper, G., Blumell, L. and Bunce, M. (2021) ‘Beyond the “refugee crisis”: How the UK news media represent asylum seekers across national boundaries’, International Communication Gazette, 83(3), pp. 195–216. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/1748048520913230.

Davy, D. (2022) ‘Trafficked by someone I know: A qualitative study of the relationships between trafficking victims and human traffickers in Albania’, UNICEF Albania & IDRA.

Department of Education (2014) ‘Statutory guidance on children who run away or go missing from home or care’, Department for Education, Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/307867/Statutory_Guidance_-_Missing_from_care__3_.pdf [Accessed: 29.06.2023]

Department of Education (2017) ‘Care of unaccompanied migrant children and child victims of modern slavery’. Statutory guidance for local authorities, Department for Education, November 2017, Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/656429/UASC_Statutory_Guidance_2017.pdf [Accessed: 29.06.2023]

ECPAT UK (no dateA) ‘Harmful Nationality and Borders Act passes – April 29th 2022′. [online]. Available at: https://www.ecpat.org.uk/news/the-nationality-and-borders-act-received-royal-assent-this-week-after-a-hard-fought-battle-to-increase-rights-and-protections. [Accessed: 13.03.2023]

ECPAT UK (no dateB) ‘Child trafficking statistics’. [online]. Available at: https://www.ecpat.org.uk/child-trafficking-statistics. [Accessed: 13.03.2023]

Gower, M., McKinney, C.J, Dawson, J. and Foster, D. (2023). ‘Illegal Migration Bill 2022-23′. Research Briefing. House of Commons Library.

Hynes, P. et al. (2019). ‘‘Between Two Fires’: Understanding Vulnerabilities and the Support Needs of People from Albania, Viet Nam and Nigeria who have experienced Human Trafficking into the UK’. United Kingdom: University of Bedfordshire, IOM, IASR.

Home Office (2020) ‘Children’s asylum claims’. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/947812/children_s-asylum-claims-v4.0ext.pdf., [Accessed: 13.03.2023]

IOM (2016) ‘Fatal Journeys, Identification and Tracing of Dead and Missing Migrants’. International Organization for Migration (IOM), 12 Aug. 2016.

IOM (2019) ‘Fatal Journeys: Missing Children’. International Organization for Migration (IOM), 18 Jun. 2019.

Jenkins, C. (2023) 154 child asylum seekers remain missing from the official accommodation in UK, 21 July 2023, Channel 4, Available at: https://www.channel4.com/news/154-child-asylum-seekers-remain-missing-from-the-official-accommodation-in-the-uk, [Accessed: 14.10.2023]

Johnson, H. (2023). ‘FactCheck: 200 unaccompanied asylum-seeking children still missing from UK hotels – what the government has said explained’. [online] Channel 4 News, 3 February 2023, Available at: https://www.channel4.com/news/factcheck/factcheck-200-unaccompanied-asylum-seeking-children-still-missing-from-uk-hotels-what-the-government-has-said-explained, [Accessed: 13.03.2023]

KIND (2020). ‘Briefing Paper and Key Recommendations Concerning Measures at EU Borders for Unaccompanied Children’. [Online], KIND, Available at: https://supportkind.org/resources/briefing-paper-and-key-recommendations-concerning-measures-at-eu-borders-for-unaccompanied-children/ (Accessed: 11 March 2023).

Neal, D. (2022) ‘An inspection of the use of hotels for housing unaccompanied asylum-seeking children (UASC), March – May 2022’, Independent Chief Inspector of Borders and Immigration, Presented to Parliament pursuant to Section 50(2) of the UK Borders Act 2007, October 2022, Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1017995/ICIBI_Annual_Report_for_the_period_1_April_2020_to_31_March_2021_Standard.pdf [Accessed 27.06.2023]

NTS (2022) ‘National Transfer Scheme Protocol for Unaccompanied Asylum Seeking Children, Version 4.0 (updated on 05 September 2022)’, Department for Education and Home Office, Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1102578/National_Transfer_Scheme__NTS__Protocol_for_unaccompanied_asylum_seeking_children__UASC_.pdf [Accessed 29.06.2023]

PBS (2023). ‘Activists say UK government not keeping asylum-seeking minors safe as hundreds go missing’. PBS. Available at: https://www.pbs.org/newshour/show/activists-say-uk-government-not-keeping-asylum-seeking-minors-safe-as-hundreds-go-missing. [Accessed: 7 March 2023].

Sanchez, G. (2018) ‘Children and irregular migration practices: missing children or missing data? On Migration policy practice’, Migration Policy Centre, 2018, VIII:2, 30-33, Available at: https://hdl.handle.net/1814/58745. [Accessed: 7 March 2023].

The Fostering Network (2023) ‘Looking after unaccompanied asylum seeking children in the UK’, The Fostering Network, Available at: https://www.thefosteringnetwork.org.uk/advice-information/looking-after-fostered-child/looking-after-unaccompanied-asylum-seeker-children (Accessed: 7 March 2023).

The Guardian (2023a). ‘The Guardian view on young asylum seekers going missing: unsafe spaces’, The Guardian. Available from: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2023/jan/23/the-guardian-view-on-young-asylum-seekers-going-missing-unsafe-spaces [Accessed: 7 March 2023].

The Guardian (2023b). ‘UK minister admits 200 asylum-seeking children have gone missing’, The Guardian. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2023/jan/23/uk-minister-admits-200-asylum-seeking-children-missing-home-office [Accessed: 13 March 2023].

The Guardian (2023c). ”They just vanish’: Whistleblowers met by wall of complacency over missing migrant children’, The Guardian. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2023/jan/21/they-just-vanish-whistleblowers-met-by-wall-of-complacency-over-missing-migrant-children [Accessed: 13 March 2023].

The Guardian (2023d) ‘UK missing child refugees put to work for Manchester gangs’, The Guardian, Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2023/feb/18/uk-missing-child-refugees-put-to-work-manchester-gangs [Accessed: 7 March 2023].

UK Parliament (2023). ‘Unaccompanied asylum-seeking children’, Commons Chamber. Available at: https://hansard.parliament.uk/commons/2023-01-24/debates/290AF292-5D7E-411C-8FB8-A6E0F288365C/UnaccompaniedAsylum-SeekingChildren [Accessed: 13 March 2023].

UK Parliament (2023) “Asylum: Children Questions for Home Office.” Written Questions, Answers and Statements, UK Parliament, 2 Mar. 2023, questions-statements.parliament.uk/written-questions/detail/2023-03-02/156968. [Accessed: 12 March 2023].

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). (1994) ‘Guidelines on Policies and Procedures in dealing with Unaccompanied Children Seeking Asylum’. Geneva: UNHCR.

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), 2021 UNHCR Best Interests Procedure Guidelines: Assessing and Determining the Best Interests of the Child, May 2021, available at: https://www.refworld.org/docid/5c18d7254.html [accessed 16 October 2023]

UNHCR (2015) ‘Press Coverage of the Refugee and Migrant Crisis in the EU: A Content Analysis of Five European Countries’. rep. Cardiff, UK: UNHCR.