by Natasha Mulvihill and Hannah Richards

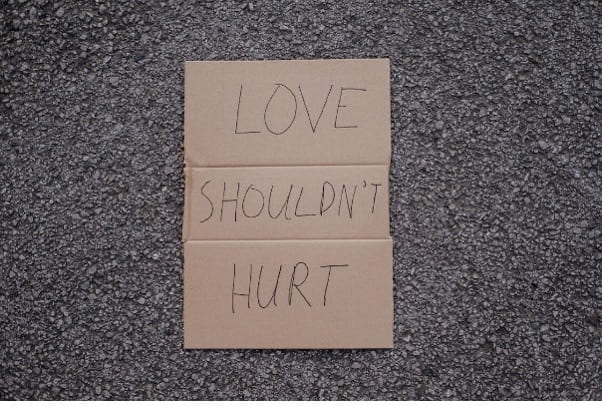

There is small but growing academic interest in experiences of so-called ‘rough sex’, particularly within younger people’s relationships and in dating culture. This work explores both wanted and unwanted experiences (see e.g. Faustino and Gavey (2021); Herbenick et al (2022), Snow (2023) Mulvihill (2022), and the use of rough sex as a tool of coercive control (Wiener and Palmer. 2022 and murder (Edwards. 2020; Bows and Herring, 2020). Commonly, this work draws on the concept of ‘sexual scripts’ (see e.g. Simon and Gagnon, 1986), which recognises how the sexual norms internalised by individuals are informed and endorsed through socialisation. For this reason, some argue that the sexual scripts of contemporary mainstream pornography are troubling (see e.g. Vera-Gray et al., 2021). Keene (2021, p.293) suggests that it “presents an assemblage of easy-to-access, misogynistic, and hostile depictions of heterosexual relationships”. This representation is consistent with what some describe as a ‘rape culture’, where heterosexual male-to-female sexual violence is eroticised. Keene argues that this is additionally problematic if holistic sexuality and relationship education is lacking (op cit.). In all this work, the concern here is not to police sexual taste, to essentialise gendered experiences of sex, or to ignore that human desire is complex and contradictory. Rather, this body of work recognises where sexual practices are experienced as coercive and upsetting (sometimes fatal), and that this harm is disproportionately experienced by women.

It is within this context that Hannah Richards, final year undergraduate Criminology student in the School for Policy Studies, embarked on her dissertation to explore how young people negotiate participation in, and consent around, ‘rough sex’. She circulated an online anonymous survey, targeting UK undergraduate or recent graduate students, of any gender or sexuality. Her survey yielded 58 responses, combining demographic, attitudinal and qualitative accounts, which she analysed using thematic analysis. Her final submission “Blurred Lines”: ‘Student Attitudes Towards Rough Sex and the Repercussions of Pain is Pleasure’ earned her a first class mark. Here, Dr Natasha Mulvihill, Associate Professor in Criminology, interviews Hannah about her research:

According to your survey participants, Hannah, why might people engage in ‘rough sex’ and how do they negotiate consent?

Both male and female participants experienced pressure to engage in ‘rough sex’, often because it is portrayed as desirable in the media. This has resulted in negative connotations surrounding conventional, or ‘vanilla’ sex, leading to a rise in interest in BDSM or ‘kinky’ behaviours. As a result, individuals may find themselves compelled to partake in activities that make them uncomfortable but feel the need to conform. Many participants expressed that this pressure often blurs the line between ‘rough sex’ and genuine passion. When it comes to negotiating consent, explicit verbal consent continues to be regarded as a taboo by participants, making the process awkward. Female participants, in particular, fear that seeking verbal consent might ‘ruin the mood.’ However, participants did recognise its importance and the need to re-establish consent throughout intercourse. Additionally, the presence or absence of consent was a defining factor in determining whether rough sex had a positive or negative impact on intimate relationships.

How did your participants define and distinguish between ‘safe’ and ‘harmful’ rough sex?

Most participants only considered rough sex to be unsafe if it involved behaviours that were unwanted, and some did not consider it to be harmful at all. However, obtaining consent played a crucial role in distinguishing safe actions from harmful ones. When defining ‘harmful’ rough sex, participants emphasise the risks that come with practices such as non-fatal strangulation. Examples of these risks included physical dangers, like loss of consciousness and cutting off blood supplies, as well as emotionally and mentally impactful acts of extreme dominance. There were also concerns expressed about individuals romanticising sexual violence or engaging in physically violent acts that reinforced harmful boundaries. However, other participants state that labelling rough sex as ‘unsafe’ might not be appropriate due to varying levels of pain tolerance among individuals. They suggested that, at times, going too far can be a “harmless mistake”.

One of your research questions was to understand how far participants feel that mainstream pornography contributes to ‘rape culture’. What did you find?

My findings demonstrate that participants certainly feel that pornography depicts sexual violence as normative and gendered, with male dominance consistently portrayed as desirable. The media’s influence in both normalising and romanticising violent acts during sexual activity was widely agreed upon. This was especially highlighted by participants’ concern over the lack of consent presented within popular websites such as Pornhub. The constant availability of rough sexual content contributes to its desensitisation, further normalising sexual violence and potentially influencing individuals to recreate what they see online. For female participants, the objectification of women within pornography was also problematic, leading to additional pressures and expectations from sexual partners. Having said that, the majority of participants were able to recognise that sexual activity depicted in pornography is not representative of ‘real-life’ encounters.

Was there anything in your research that surprised you?

Despite extensive study of the topic over the months, I was still shocked by some of the responses. For example, one male participant expressed the disturbing view that women ‘should expect’ acts like non-fatal strangulation.. This observation served as a striking example of how cultural scripts of male dominance manifested in my research. It also left me disheartened by the apparent lack of education regarding the impact of such attitudes. Additionally, I was taken aback by the common belief among my participants that consent is less relevant in longer-term relationships. A majority of survey respondents suggested that that, once a new sexual act receives consent in such relationships, there is no need to re-establish it for subsequent encounters. This illustrates how sexual violence and harm can emerge within intimate partner relationships.

What do you think are the practical implications of your research, and for whom?

Aside from the implications for education and awareness in sex and relationships, this research also raised ethical questions. Even though my sample did not include any vulnerable groups, I had to make several revisions to my survey questions in order to obtain ethical approval and ensure that no participants felt unduly uncomfortable or upset. Additionally, I had to take measures to minimise potential risks to myself as the researcher. This proved to be challenging since the subject matter is intrinsically sensitive. It raises the question of how we do difficult but much-needed research in a safe way. Overall however, my passion for the topic made the effort entirely worthwhile.

Congratulations to you on an excellent piece of work! You have shown how students can use the final year dissertation to engage in current issues and to develop their skills in project planning, ethical awareness and analysis. We wish you well in whatever you do next.

Hannah would like to thank her undergraduate dissertation supervisor, Dr Vicky Canning, and her friends and family for supporting her during her final year.