by Natasha Mulvihill and Hannah Richards

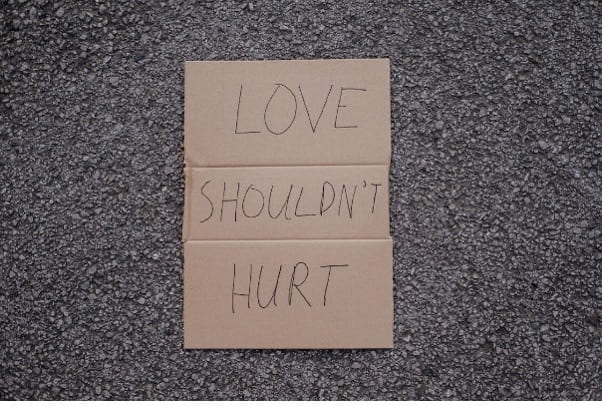

There is small but growing academic interest in experiences of so-called ‘rough sex’, particularly within younger people’s relationships and in dating culture. This work explores both wanted and unwanted experiences (see e.g. Faustino and Gavey (2021); Herbenick et al (2022), Snow (2023) Mulvihill (2022), and the use of rough sex as a tool of coercive control (Wiener and Palmer. 2022 and murder (Edwards. 2020; Bows and Herring, 2020). (more…)

This post by Paul Willis, Brian Beach and

This post by Paul Willis, Brian Beach and