Dr Gözde Doğanyılmaz-Burger, Senior Research Coordinator at the University of Bristol, reflects on the sessions she chaired at the first International Child and Family Conference held in Bristol on 17-19 June, and the questions those sessions set out to answer:

-

How are children’s voices recognised (or dismissed) in legal, policy and everyday decisions that shape their family lives?

-

How do caregiving expectations, policy design, and labour markets affect family life and gender equality?

Session 1: Children’s agency, participation, and family transitions

On day two of the conference, I had the pleasure of chairing and presenting in a powerful session on Children’s Agency and Participation, a topic close to my heart and the focus of my PhD research.

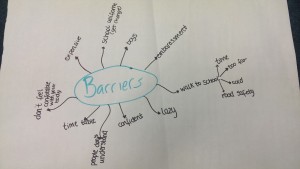

The session featured four studies that offered unique insights into how children’s voices are heard (or silenced) in matters that deeply affect them:

Children’s experiences of parental separation

Dr Susan Kay-Flowers explored 25 years of international research on children’s experiences of parental separation, highlighting ethical dilemmas around participation and voice.

Father-child contact after domestic violence

Prof Simon Lapierre and Ms Naomi Abrahams shared findings from Canada on children’s participation in decisions about father-child contact after domestic violence, proposing information as a critical fifth dimension to Lundy’s model.

Children’s rights and family law

Prof Maebh Harding and Dr Jakub Pawliczak challenged us to rethink constitutional conservatism in Ireland and Poland and asked whether children’s rights can drive more inclusive family law.

Communication during divorce

And I presented my research comparing young people’s experiences in Türkiye and England, focusing on how communication (or lack of it) during divorce shapes their emotional wellbeing, agency and rights.

Each presentation sparked important questions about children’s legal, psychological and emotional needs, and how research, policy and practice can respond more meaningfully.

Thank you to the presenters and all who joined the discussion. It was a joy to be part of this international conversation on centring children’s voices in family transitions.

It was extra special to share my findings on Turkish and English young people’s experiences of divorce-related communication, and to have my main supervisor, Prof Debbie Watson, whose guidance has been invaluable throughout my PhD, in the room, along with my mum Prof Nesrin Özsoy-Bür, who travelled all the way from Türkiye to support me (especially with childcare!).

Session 2: Care, family policy, and the everyday experiences of work-life balance

On the final day of the conference, I had the privilege of chairing another incredible session, this time focused on care, family policy, and the everyday experiences of work-life balance.

It was a joy to listen to such rich, thought-provoking presentations that explored how policy, labour markets, and social expectations shape caregiving, while also highlighting the voices, presence, and roles of children and families so often left out of mainstream narratives.

Caregiving responsibilities and gender inequality

Ms Curran McSwigan (Deputy Director of the Economic Program at Third Way, USA) presented a powerful analysis of how caregiving responsibilities continue to drive gender inequality in the US labour market, particularly for women without a college degree. Her research reminded us how the absence of robust childcare and paid leave policies contributes to ongoing cycles of disadvantage for women and children.

Work-family reconciliation policies

Dr Manisha Mathews (University of Birmingham, UK) critically examined the UK’s work-family reconciliation policies, arguing that current policy design still reflects the “male breadwinner” model and limits fathers’ ability to participate in childcare. Her comparison with the Nordic model underscored the value of long, well-paid leave for both parents in promoting children’s cognitive and emotional wellbeing.

Home as both the family and work hub

Dr Jana Mikats (Webster Vienna Private University, Austria) introduced the concept of dense, intimate knowledge, referring to children’s deep, nuanced awareness of their parents’ work when that work is done at home. Her ethnographic study of Austrian families challenged traditional boundaries between “work” and “family”, offering a fresh lens on intimacy, co-presence, and children’s everyday lives in digitally shaped households.

In our discussion, we reflected on how policy and discourse often centre around nuclear, heterosexual, two-parent families, excluding the lived realities of single-parent households, blended families, grandparents, friends, and broader networks of care. There was a clear call to recognise and support the many ways care is provided beyond dominant family models.

I’m grateful to have chaired such a thoughtful and intersectional session and for the opportunity to connect research across disciplines and contexts.