An account of an article by Dr Nazand Begikhani’s first published in France’s Le Monde on 23 January.

A recent statement signed by 100 French women, including Catherine Deneuve (Le Monde, 8 January) criticised the #MeToo campaign and defended the right of men to ‘importune’ in the name of ‘sexual freedom’, claiming that men have been subjected to a ‘witch-hunt’. Both the statement and Deneuve’s response (Liberation, 14 January) advocated that such cases should be left to justice institutions, away from ‘public euphoria’.

I contributed to the debate by publishing an article questioning the nature of justice for women in cases of rape and sexual harassment. Quoting Albert Camus’s famous phrase, ‘between justice and my mother, I chose my mother’, my article highlights the fact that the #MeToo campaigners, like Camus, are not opposed to justice not to men, but to patriarchal ‘violence’, if not ‘terrorism’.’

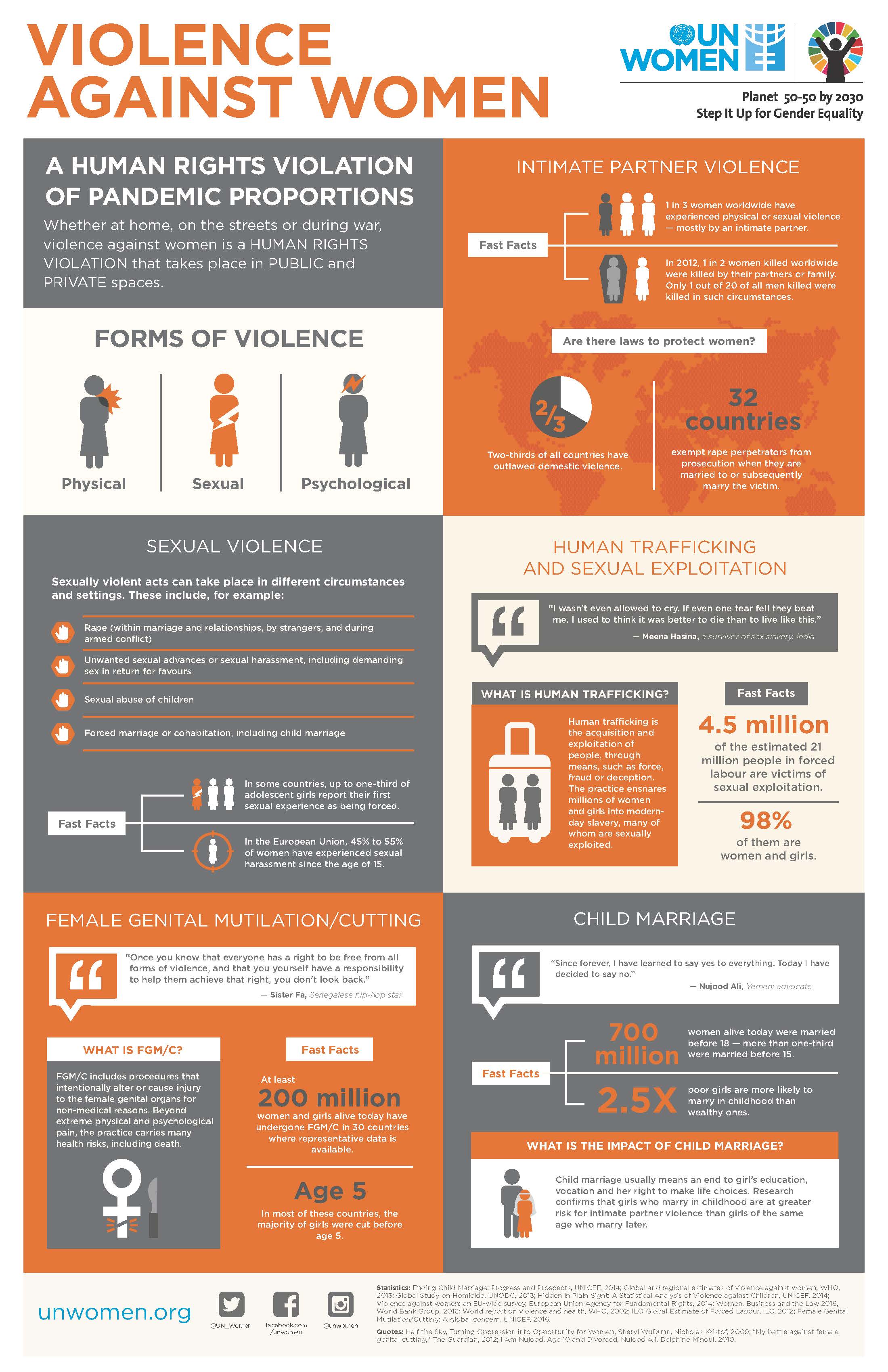

The article entitled ‘La justice est en retard vis-à-vis des femmes victimes’, refers to studies conducted by our Centre for Gender and Violence Research (CGVR), indicating that criminal justice system is short in establishing the rights of women when it comes to abuse and harassment. It adds that in certain countries, such as Iraq, the law forces raped women to marry their rapists to save the honour of their families.

In Western countries where new strategies have been adopted, it is difficult to bring abusers to justice and when it happens they are rarely condemned. Studies conducted by our Centre affirm that the criminal justice system, which is based on ‘incidence’ approach, undermines their emotional and psychological suffering of women and rarely lead to the condemnation of alleged criminals. Le Monde, via my article, highlights that this approach counters the UN Declaration on the Elimination of Violence Against Women (1993), which stipulates in its definition of Violence Against Women (VAW) all forms of ‘physical, emotional and psychological’ violence. It reiterates that the public mobilisation and feminist campaigns can have an impact leading to justice in cases of VAW.

The article concludes that, in many places, including in Paris’ suburban zones, in refugee camps in Calais, inside migrant communities as well as in many southern and Mediterranean countries, women could not join the #MeToo campaign to denounce their abusers, fearing revenge and retribution. It is regrettable that Deneuve’s statement, instead of helping such women in coming forward and expressing themselves, helped reactionary and extremist figures such as Berlusconi who felt he was ‘blessed’ by the statement.

The full article (in French) ‘La justice est en retard vis-à-vis des femmes victimes’ was published in Le Monde on 23 January.