This blog by Shunsuke Tani draws on a Policy Brief he submitted recently as an assessment for the Governance, Institutions and Global Political Economy unit on the MSc Public Policy programme here in the School for Policy Studies. It discusses the risks and policy challenges associated with money laundering which relies on Virtual Assets—or ‘crypto-currencies’—and the policies that have been introduced to regulate them. There were many excellent student submissions, but Shunsuke’s policy brief was awarded the highest mark overall.

Introduction

As financial transactions are growing more sophisticated and international, and enabled through technological advancements, the increasing diversity of settlement methods, and the risks faced by financial institutions in money laundering are also evolving. Money laundering using virtual assets (VAs) is attracting particular attention. VAs emerged both as a novel form of currency and an advanced payment method to get goods and services. But VAs threaten the existing measures of anti-money laundering because they also have an anonymous aspect which makes it difficult to track down who actually owns them. International organisations and governments are rushing to prevent people from using VAs to launder money. This blog provides an overview of the risks of money laundering using VAs around the world, the policies introduced in the USA, the UK and by international organisations, and the policy challenges involved in regulating anti-money laundering using VAs.

Virtual Assets and Money Laundering

In one year, 2-5% of global GDP is estimated to be laundered (UN, no date) with translates into approximately $2-5 trillion (IMF, 2022). This amount is equivalent to the GDP of Japan, the third-largest economy, indicating that this is a global challenge on an exceptionally large scale. Money laundering using VAs has become a particular issue of concern. VAs have emerged both as a novel form of currency and an advanced payment method to get goods and services (see Table 1). The incorporation of cryptographic identifying methods into a “blockchain” is their main invention: a digital record that enables the tracking and validation of all payments made. Bitcoin, which is representative of VAs, was launched in 2009 and caused a stir amongst the financial press, economists and governments (Bolt and Van Oordt, 2019). However, the anonymity and lack of transparency associated with VAs pose a potential threat to existing anti-money laundering measures (Campbell-Verduyn, 2018). International Organisations and governments have rushed to introduce measures to contain these activities but the struggle with technological innovation and effective policy measures continues.

Table 1: Representative VAs on 9th May 2023

Money laundering using Virtual Assets

a) Cyber-attacks, money laundering and VAs

Ransomware cyber-attacks using VAs are on the rise. Ransomware is malware that uses encryption to hold the victim’s information hostage for ransom. Typically, the users cannot access critical data until the ransom is paid. Taking advantage of the characteristics of VAs, these ransoms are often demanded in Bitcoin. In 2017, one of the biggest assaults ever was the Wannacry Ransomware outbreak and around 300,000 computers in hospitals and banks in 150 countries were held hostage (Trellix, 2022). The worldwide damage is estimated at $8 billion, far exceeding the actual ransom demand (FATF, 2022).

b) Unauthorised transfer of funds via VAs to high-risk jurisdictions

VAs are exploited for money laundering in high-risk where there are significant deficiencies in regulations to deter money laundering and address risks associated with the anonymity of VAs.

Policy responses and challenges

In the USA companies are required to register with the government if they sell VAs to users. Focusing on anti-money laundering, the government requests VA Service Providers (VASPs) to develop and implement suspicious transaction reports to deter their use of money laundering and financial terrorism. However, these regulations are exceedingly abstract and have been assessed as struggling to control the wide range of financial transactions in decentralised finance, resulting in regulatory gaps. In the UK the Financial Conduct Authority requires registration if companies sell VAs to users. In addition, VASPs are required to follow anti-money laundering rules which provide for the development of a system based on the identification and assessment of anti-money laundering risks in the business, the screening of users and the powers of supervisory authorities. The UK was identified by the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) as one of the best-rated countries. However, some argue is indicative of policy indecision because there remains ambiguity about regulated VAs.

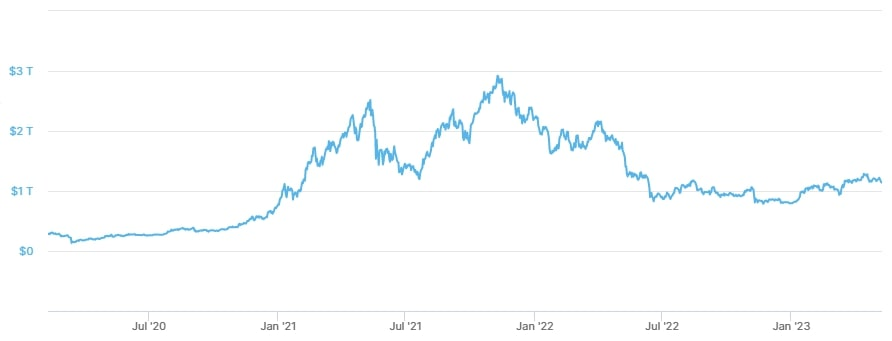

The Financial Action Task Force (FATF) is an international organisation which establishes worldwide standards and creates policies to combat money laundering and financial terrorism. FATF released a series of 40 recommendations in 1990 to direct anti-money laundering. With regard to VAs in particular, FATF took the opportunity at the G7 Summit in 2015 to recommend governments enforce a licensing system for VASPs in every country. On top of this, in 2019, FATF amended a recommendation to impose on VASPs the verification and storage of information on their senders and receivers, known as “travel rule” (Lee et al., 2022). Countries are currently developing legislation to follow this; but, due to differences in security, data protection and anti-money laundering requirements in each country, the potential risk of crime in countries with weaker regulations is a real concern (Altankhuyag, 2020). The International Monetary Fund (IMF) is particularly concerned with VAs, not just from an anti-money laundering perspective, but also from the standpoint of global financial stability. VA’s infiltration of the conventional financial system with their aggregate market value, whilst unstable, skyrocketed to almost $3trillion in November 2021 (Figure 1).

Figure 1: The aggregate market values of VAs

Policy Evaluation

VAs have many potential benefits in that they are simple, fast, and reduce costs; what is more, they offer an alternative for individuals without access to traditional financial instruments which can improve financial inclusion. However, according to FATF, only 58 of the 128 reporting countries have regulated VASPs, which means 70 countries don’t incorporate VASPs into their regulation. Also, the cross-border and non-transparent nature of VAs make regulation and enforcement tricky, provoking a “regulatory gap” between nations. Without a common worldwide approach, entities might relocate to laxly-regulated jurisdictions and evade regulation. Therefore, bridging the gap is an essential challenge to address and minimise VA-related anti-money laundering risks and shore-up global financial stability.

Policy Recommendation

Currently, in the VA field, although irregular meetings have been held, no international organisation has been established specifically for VAs. Considering the issues discussed so far, this would seem to be an essential, effective and efficient strategy to begin to address the challenges outlined above. The establishment of an international organisation would encourage the standardisation of responses in each country, leading to the elimination of regulatory ambiguity, drawing together and complimenting the work of FATF and other international organisations.

The introduction of an international organisation would energise and prioritise debate on VA-specific issues, as well as address the issue of “travel rule” with criminal activity attracted to nations which are more laxly regulated. In addition, it would provide a knowledge exchange forum and could support countries that don’t yet have institutional arrangements or the infrastructure to effectively regulate and protect.

References

Abutaleb, Y. and Cooke, K. (2016). A U.S. teen’s turn to radicalism, and the safety net that failed. [online] Reuters. Available at: https://www.reuters.com/investigates/special-report/usa-extremists-teen/ [Accessed 5 Dec. 2022].

Altankhuyag, T. (2020). The AML ‘travel rule’: a new challenge for VASPs and GDPR. [online] GRC World Forums. Available at: https://www.grcworldforums.com/financial-crime/the-aml-travel-rule-a-new-challenge-for-vasps-and-gdpr/236.article [Accessed 6 Dec. 2022].

Bolt, W. and Van Oordt, M.R.C. (2019). On the Value of Virtual Currencies. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 52(4). doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/jmcb.12619.

Campbell-Verduyn, M. (2018). Bitcoin, crypto-coins, and global anti-money laundering governance. Crime, Law and Social Change, [online] 69(2), pp.283–305. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10611-017-9756-5.

CoinMarketCap (2022a). Cryptocurrency Market Capitalizations | CoinMarketCap. [online] CoinMarketCap. Available at: https://coinmarketcap.com/ [Accessed 8 5 Mar. 2023].

CoinMarketCap (2022b). Global Charts | CoinMarketCap. [online] CoinMarketCap. Available at: https://coinmarketcap.com/charts/ [Accessed 11 5 Mar. 2023].

FATF (2022). Virtual Assets. [online] www.fatf-gafi.org. Available at: https://www.fatf-gafi.org/publications/virtualassets/documents/virtual-assets.html?hf=10&b=0&s=desc(fatf_releasedate) [Accessed 5 Dec. 2022].

IMF (2022). GDP, current prices. [online] www.imf.org. Available at: https://www.imf.org/external/datamapper/NGDPD@WEO/OEMDC/ADVEC/WEOWORLD/RUS [Accessed 6 Dec. 2022].

Lee, C., Kang, C., Choi, W., Cha, M., Woo, J. and Hong, J.W.-K. (2022). CODE: Blockchain-based Travel Rule Compliance System. [online] IEEE Xplore. doi:https://doi.org/10.1109/Blockchain55522.2022.00038.

Trellix (2022). What Is Ransomware? | Trellix. [online] www.trellix.com. Available at: https://www.trellix.com/en-us/security-awareness/ransomware/what-is-ransomware.html.

UN (n.d.). Overview. [online] United Nations : Office on Drugs and Crime. Available at: https://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/money-laundering/overview.html [Accessed 4 Dec. 2022].